How to search the page

iOS Safari – tap the action icon (square with arrow at bottom of screen) and select ‘find on page’ from the list of options.

Other mobile browsers – tap the browser’s options menu (usually 3 dots or lines) and select ‘find on page’ from the options.

CTRL + F on your keyboard (Command + F on a Mac)

This will open a search box on the page. Type the word you are looking for in the search box and press enter. The word will then be highlighted wherever it appears in the guidance. Use the navigation in the search box to move to the next word found.

How to print a copy of the page

iOS Safari – tap the action icon (square with arrow at bottom of screen) and select ‘print’ from the list of options.

Other mobile browsers – tap the browser’s options menu (usually 3 dots or lines) and select ‘print’ or select ‘share’ from the list of options, then ‘print’ in the popup.

CTRL + P on your keyboard (Command + P on a Mac)

You have an option to print the entire page, or select a page range.

Purpose of the document

This evidence base sets out the Council’s reasoning and justification for making an Article 4 Direction under the provisions of the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) Order 2015 (as amended) to remove permitted development rights for the change of use from dwelling-houses (Use Class C3) to small houses in multiple occupancy (HMOs) (Use Class C4).

This document should be read in conjunction with the Consultation Statement.

Overview and historical background

Blackpool faces unique and extreme challenges which are rooted in the Blackpool’s changing fortunes as the UK’s largest seaside holiday resort.

Traditionally, the holiday accommodation offer in Blackpool largely took the form of small, family-run guest-houses. Changes in visitor expectations starting in the 1960s led many operators to convert their properties into small, but self-contained, holiday flats. As these conversion works were internal, and as the holiday use of the property continued, these changes went undetected by the Council and subsequently became lawful through the passage of time, without any restrictions on occupancy.

More than three decades of decline in the tourism economy starting in the later 1970s saw many former guest-house and holiday premises used to provide permanent accommodation. In many cases this was a gradual change as operators took in more winter-lets and allowed more residents to stay on through the season to supplement their holiday income. Thus holiday flats became permanent flats and guest-houses became HMOs. Again, these uses became lawful through the passage of time. While the former guest-house and holiday flat owners continued to live on site, these premises were generally well-managed, and the accommodation, though small, was well-maintained in many cases.

As years passed and the decline of the tourism economy continued, former holiday accommodation premises were increasingly bought up by out-of-town investors who had no stake in or commitment to the Blackpool community. Accommodation became dated and fell into poor condition, and there was much reduced impetus for remote landlords to vet prospective tenants or manage properties with care.

By the 1990s the extent of the problems were becoming very apparent and this is reflected by the Council’s introduction of standards in 1999 to try and improve the quality of new residential accommodation created through conversion. By then, however, the housing stock of the defined Inner Areas was already overwhelmingly dominated by small, privately-rented, poor-quality and poorly managed accommodation. This accommodation attracted those who were not in a position of choice and resulted in a highly transient population often characterised by vulnerable individuals with chaotic lifestyles. Many of these people were from outside the area and this remains the case today as approximately 80% of privately-rented accommodation is occupied by people on housing benefit, and 86% of new claimants originate outside of the borough.

The consequence of this legacy is a skewed and imbalanced housing stock; a marked lack of community cohesion, and extremely high levels of deprivation. The availability of low-cost accommodation continues to make Blackpool attractive to low-income and vulnerable households, and this reinforces the demand for this type of accommodation creating a vicious cycle.

Away from the defined Inner Area, the housing stock is generally of a much better standard and is typically dominated by family housing. Social cohesion in these areas is far more robust and deprivation levels are significantly lower. The Council considers it essential to safeguard the character of these areas to ensure that they remain attractive to those who are in a position of choice and will contribute economically and socially to establishing Blackpool as a sustainable and desirable place to live and work.

Blackpool’s profile:

Deprivation

The 2019 Indices of Multiple Deprivation ranked Blackpool as the most deprived area nationwide in terms of average rank, average score, and local concentration. Blackpool suffers from the most concentrated deprivation in the country and ranks as 12th worst in terms of the extent of deprivation.

Table 1 shows levels of deprivation within Blackpool with regard to specific indicators. Each Local Authority area is split into lower super-output areas (LSOA). For each indicator of deprivation these LSOAs are awarded a score and a rank out of 32,844. These LSOA scores and ranks are then used to calculate the rank and score of the Local Authority area as a whole. The ranks listed under table 1 show Blackpool’s position relative to the other 316 Local Authority areas in the country.

Table 1: Deprivation in Blackpool

Deprivation in Blackpool

| Type | Rank of average rank | Rank of avergae score |

|---|

| Income |

1 |

|

| Employment |

2 |

1 |

| Education, skills and training |

8 |

9 |

| Health |

1 |

1 |

| Crime |

16 |

8 |

| Barriers to services |

308 |

308 |

| Living environment |

15 |

12 |

| Child deprivation |

6 |

2 |

| Older person deprivation |

18 |

24 |

Population and household composition

Blackpool has a population of around 139,300. People aged 50-59 make up the largest group at 15%. Some 23% of the population is under 20 years of age and less than 10% are over 75. Overall there are significantly more people over the age of 45 in Blackpool than there are nationally, and therefore a considerably lower proportion of people aged 20-44.

In 2011 the Office for National Statistics (ONS) recorded just over 64,300 households in Blackpool. Of these, 38% were single-person households. This compares with a national average of just over 30%. The proportion of single-person households aged 65yrs as a percentage of the total is around 40% for both Blackpool and England as a whole and this suggests a significantly larger proportion of younger people living alone.

The total population of Blackpool is projected to fall very gradually from some 140,000 in 2016 to around 136,500 in 2041. This population decline is expected to come from natural change with deaths exceeding births. Immigration into Blackpool is anticipated to fall in the short term, level off towards the end of the 2020s and then increase again thereafter. This increase is expected to balance the natural population decline leading to a levelling off in total population as we approach 2041[1].

Employment and income

In terms of employment, the ONS figures show that 66% of the Blackpool working-age population is economically active compared to 70% nationwide. Long-term unemployment is half as much again as the England average[2]. In terms of households, in 2019 some 20% we classed as ‘workless’ compared to 16% across the North West[3]. It is worth noting that students make up just 3.7% of the economically inactive population in Blackpool compared to 5.8% across the country.

Income levels are similarly reduced in Blackpool. In 2020, weekly pay in Blackpool averaged at £459 - compared to £560 across the North West. This was the 4th lowest rate in Great Britain and was 21% lower than the national average[4]. The disparity becomes more significant when disposable income is considered. The average salary after housing costs in Blackpool is £19,616 compared to £25,301 across the North West (around 78%). In the central areas of town, however, the average salary is around £15,000 or 59% of the North West average[5]. Blackpool also has a significantly higher benefit claimant count than the North West (12% compared to 7%) and the highest rate is within the 18-21 year old age group[6]. In 2016, just over 26% of children under 16 years of age were in low income families[7].

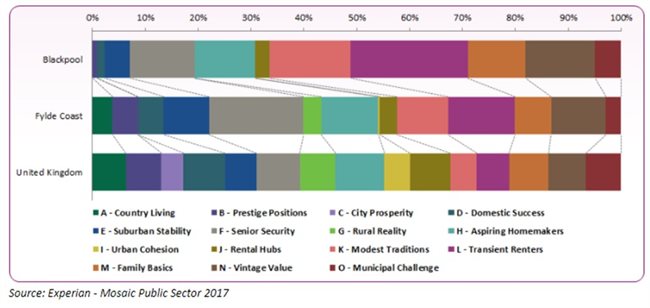

Experian use a demographic profiling tool called MOSAIC which categorises all households and postcodes into ‘segments’. These share statistically similar behaviours, interests or demographics. Whilst it is recognised that this approach makes generalised categorisations, it is a useful tool to build a picture of the characteristics of an area.

It is noteworthy that 22% of Blackpool households are classified as ‘transient renters – single people privately renting low cost homes for the short term’. A further 11% are ‘family basics – families with limited resources who have to budget to make ends meet’. ‘Vintage value – elderly people reliant on support to meet financial or practical needs’ make up another 13%. An additional 5% are categorised as ‘Municipal challenge – urban renters of social housing facing an array of challenges’. Together these categories make up 51%, over half of Blackpool’s population[8].

[1] Blackpool Joint Strategic Needs Assessment 2021

[2] ONS census data obtained from www.nomisweb.co.uk

[3] Blackpool Strategic Needs Assessment produced by the Lancashire Violence Reduction Network

[4] Blackpool Strategic Needs Assessment produced by the Lancashire Violence Reduction Network

[5] ONS - Average household income after housing costs, income estimates for small ares, England and Wales, financial year ending 2018

[6] Blackpool Strategic Needs Assessment produced by the Lancashire Violence Reduction Network

[7] Blackpool Strategic Needs Assessment produced by the Lancashire Violence Reduction Network

[8] Blackpool Joint Strategic Needs Assessment 2021 quoting Experian Mosaic Public Sector 2017

Figure 1 below is taken from the Blackpool Joint Strategic Needs Assessment and illustrates how the situation in Blackpool compares to that across the Fylde Coast and nationally. This clearly shows that a significantly higher proportion of households in Blackpool struggle to meet their basic needs and are either dependent upon support or careful budgeting (the purple, orange, brown and dark red sections).

Figure 1: Experian demographic household profiling

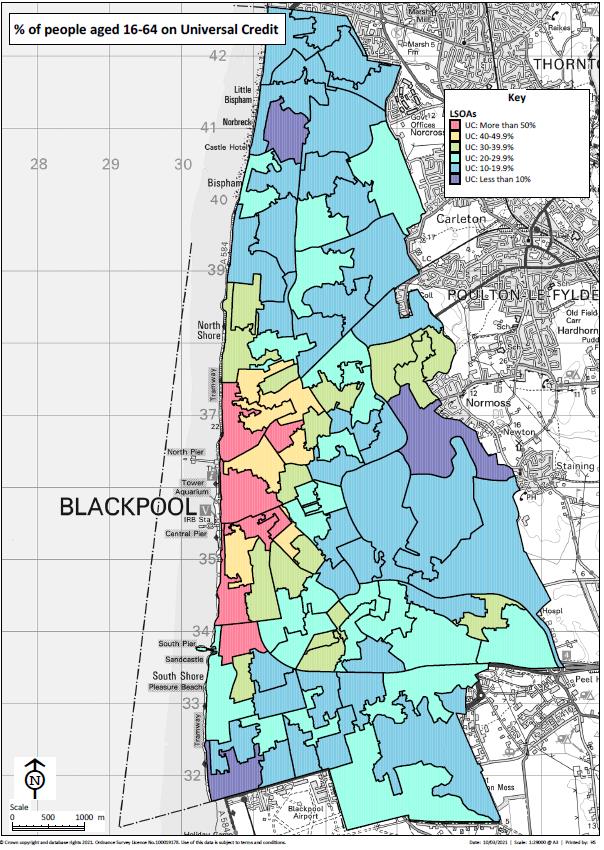

Figure 2 shows the proportion of people aged 16-64 who claim Universal Credit across Blackpool by Lower Super Output Area (LSOA). It is based on provisional figures for January provided by the Department for Work and Pensions.

Figure 2: Concentration of Universal Credit claimants within Blackpool

Housing

When Census data providing local and national information on household spaces is compared, it is appears that shared dwellings make up a very small proportion of the total housing stock. Nevertheless, Blackpool still offers twice the national average. Vacancy rates are also around 3% higher than average in Blackpool[9].

A clear difference between the local and national housing stock is the low proportion of detached dwellings (8.5% compared to 22.3%[10]) and this indicates the high housing densities that exist across Blackpool but most particularly within the defined Inner Area. Overall Blackpool has ten times the number of people per square kilometre than the average for England and Wales[11]. It is also notable that the proportion of accommodation of the form of flats in residential properties or shared houses, or in commercial buildings (e.g. flats above shops) is nearly double the national average.

Across Blackpool as a whole, levels of home ownership are not dissimilar to those across the country. Levels of shared ownership and social rental however are much reduced. The private rented sector in Blackpool accounts for more than 26% of the total stock in Blackpool compared to 17% in England as a whole[12].

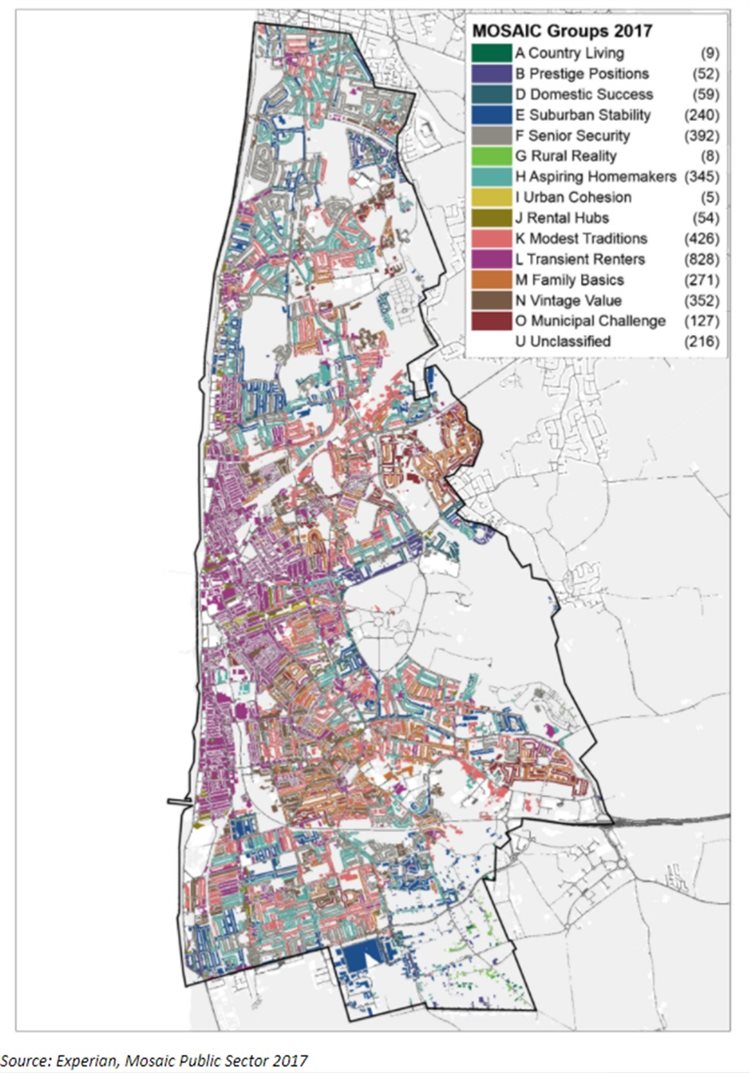

Transience has long been recognised as an issue in Blackpool. Population turnover statistics identify that some areas in Blackpool have extremely high levels of population inflow and outflow. The ‘South Beach’ area of Blackpool, for example has an inflow rate that is one of the highest in the country, within the top 1%[13]. The Experian MOSAIC data breaks the demographic segments shown in figure 1 into more detailed categories. This reveals that some 17% of Blackpool’s population comprises ‘transient renters of low cost accommodation often within subdivided older properties’. This more detailed category is by far the single largest component of the Blackpool population, accounting for twice as many residents as any other segment. A further 4% of the ‘transient renters’ are ‘maturing singles in employment who are renting short-term affordable homes’.

Figure 3 shows that, whilst these lower income households are strongly focused within the defined Inner Area, there is nevertheless a notable degree of dispersion across the borough.

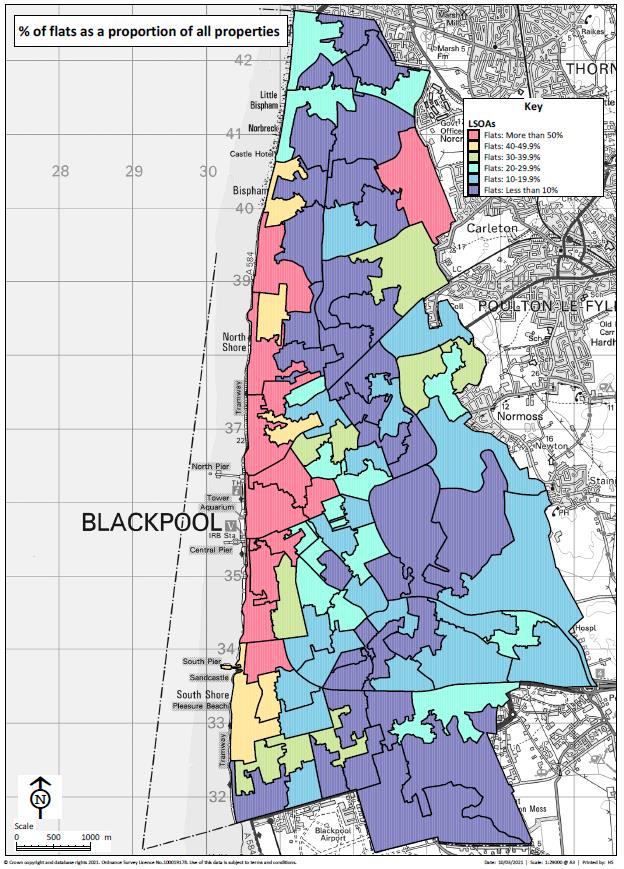

Figure 4 illustrates the concentrations of flat accommodation as a percentage of all property types across Blackpool by Lower Super Output Area (LSOA). It clearly shows that the highest proportions of flat accommodation correlate with the areas dominated by transient renters.

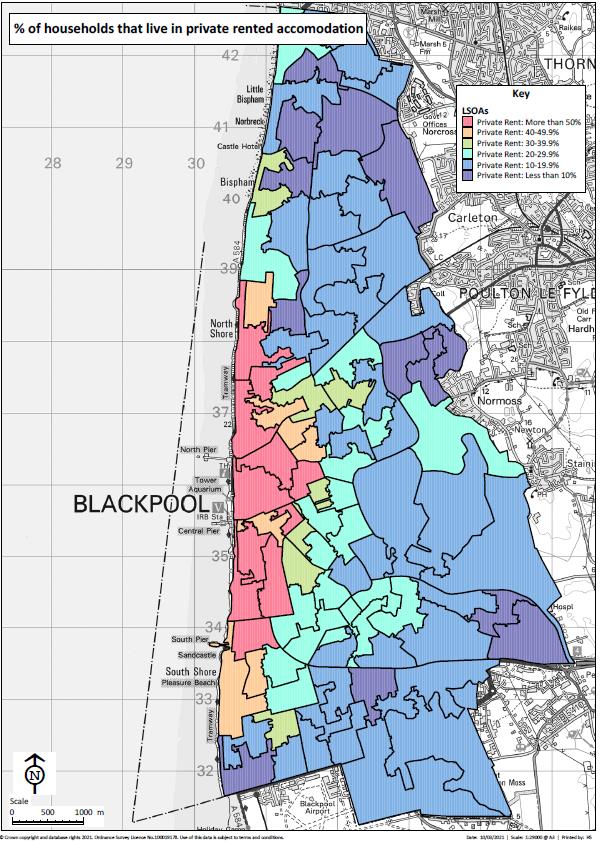

Figure 5 maps privately rented accommodation as a proportion of all households across Blackpool by LSOA. Again, the highest concentrations of privately rented accommodation correlate with the concentrations of transient renters and flat accommodation.

[9] ONS census data obtained from www.nomisweb.co.uk

[10] ONS census data obtained from www.nomisweb.co.uk

[11] Blackpool Strategic Needs Assessment produced by the Lancashire Violence Reduction Network

[12] ONS census data obtained from www.nomisweb.co.uk

[13] Blackpool Joint Strategic Needs Assessment 2021 – the Middle Super Output Area (MSOA) containing ‘South Beach’ is 65th highest in term of population inflow out of 7,194 MSOAs in England.

Figure 3: Spatial distribution of Experian demographic household profiles

Figure 4: Flats as a proportion of all properties by SLOA across Blackpool

Figure 5: Privately rented accommodation as a proportion of all households across Blackpool by LSOA

Blackpool has a relatively depressed housing market. In 2019, median house prices were well below the UK average at £110,500 compared to £256,000 across England[14]. This naturally makes property particularly affordable. Whilst the average rental value of a family home is £563 pcm, a small HMO for 3 to 6 people with rents set at Local Housing Allowance Rates people can achieve a rental of £845-£1,690 pcm[15]. They are therefore desirable prospects for developers.

The Council’s Housing Strategy 2018-2023 lists improvement of the private rented sector, including a reduction in housing density, as a key priority over the plan period. This document notes that, despite the low house prices, renting in Blackpool is more expensive and less affordable to local residents than elsewhere in Lancashire. The median monthly private sector rent was 30% of gross median salary. This compares to 21-23% in Blackburn, Burnley, Lancaster and Preston. This reflects the low salary levels in Blackpool but also illustrates the degree of dependency upon Housing Benefit.

The total number of households in receipt of housing benefit in 2013 was 14,980 or roughly a quarter. The proportion of housing benefit claimants living in the private rented sector in Blackpool is around 73% which is the highest in the country. Some 80% of all private rented tenants are in receipt of Housing Benefit. Only 22% of private renters receiving Housing Benefit are in employment.

The Council’s Housing Strategy makes it clear that the focus for future housing delivery must be on quality. In particular it notes that, within the inner areas of the town, there is a lack of choice, with too many small flats for rent and a lack of larger properties suitable for family occupation. Outside of the inner areas the housing stock is generally of a better standard, but there is still a lack of the very best new homes.

With regard to the private rented sector, the strategy acknowledges its role but considers it critical that the range and quality of homes is improved, with less emphasis on housing people dependent upon Housing Benefit. The stock must become more diverse and more attractive to tenants with good incomes. In respect of the older population, there is expected to be a 19% increase in the proportion of the population over 65 years, but this will be dominated by those over 85 due to an expected outmigration of those aged 55 and above. This older cohort would require specialist housing with level access designed or adapted to meet their specific needs[16]. Generally speaking, C4 HMO accommodation would not be suitable to meet this anticipated future need.

Health and living environment

The 2019 Public Health England Blackpool Local Authority Health Profile identifies that the health of people in Blackpool is generally worse than the England average.

Life expectancy is 12.3 years lower for men and 10.1 years lower for women in the most deprived area of town compared to the least deprived areas. Alcohol-related harm and self-harm hospital admissions exceed the national average. Levels of smoking prevalence and physical activity are worse than average across England. Blackpool suffers from worse than average rates of hip fractures in older people, sexually transmitted infections, road deaths and injury, homelessness and violent crime. Mortality rates from cardiovascular disease and cancer are also worse than the national average[17].

In terms of child health, 24% of Year 6 children are classified as obese. This, the rate of alcohol-specific hospital admissions, teenage pregnancy, GCSE attainment, breastfeeding and smoking in pregnancy are all worse than the English average[18].

The links between poor housing and poor health outcomes are well established[19]. Poor-quality housing is associated with increased risk of accident, cardiovascular disease and respiratory disease[20]. Insecure, poor quality and overcrowded housing causes stress, anxiety and depression, and exacerbates existing mental health conditions[21]. In 2015-2016 28% of homes in the private-rented sector failed to meet Decent Homes Standards compared to 19% of all homes. Common issues reported were cold conditions, damp and lack of adequate insulation[22]. In Blackpool, the 2008 Private Sector Housing Condition Survey found that around half of HMO properties failed to meet the Decent Homes Standard. In 2020 The Health Foundation reported that over-crowding, lack of access to outdoor space and poor security were linked to poor health[23]. BRE note that access to daylight and sunlight is a vital part of a healthy environment[24]. The importance of natural light is highlighted by its inclusion as a matter for consideration as part of prior approval planning applications that relate to the creation of residential accommodation.

Blackpool, and the easy availability of poor-quality rented accommodation, is known to attract vulnerable people seeking to escape other areas. Around 48% of drug related deaths in Blackpool occur among the 17% of ‘transient renters of low cost accommodation often within subdivided older properties’ identified by Experian[25]

Anti-social behaviour (ASB) and crime

The Housing Act 2004 allows Local Housing Authorities to designate areas for Selective Licensing to support the improvement of privately rented properties, providing certain conditions are met.

The definition of an HMO under the Housing Act is somewhat different to the planning definition. In general terms, a property occupied by two separate households of three or more people classifies as an HMO under the Housing Act. In contrast with planning, this can include self-contained accommodation. Notwithstanding these technical distinctions, the HMOs under both Acts are generally similar in character.

In Blackpool, the first Selective Licencing area was established in 2012 at South Beach and related to HMO accommodation. The report to the Council’s Executive Committee explains that the designation was considered necessary to tackle high levels of anti-social behaviour in the area, and to improve the quality and management of rented accommodation[26]. This initial scheme ran for 5 years. A review in 2017 identified that the number of prosecutions, notices and schedules served in respect of poor property conditions fell from over 250 to just over 50 over the 5 years[27].

[14] Blackpool Strategic Needs Assessment produced by the Lancashire Violence Reduction Network

[15] Local housing allowance rates (blackpool.gov.uk) in 2021 this is set at £65pw for a room in a shared house

[16] Blackpool Council Housing Strategy 2018-2023

[17] Public Health England Blackpool Local Authority Health Profile 2019

[18] Public Health England Blackpool Local Authority Health Profile 2019

[19] Chartered Institute of Environmental Health – Good Housing Leads To Good Health 2008

[20] Houses of Parliament – Housing and Health – post note no. 371 – January 2011

[21] Public Health England guidance on mental health: environmental factors – October 2019

[22] DCLG English Housing Survey 2015-16

[23] The Health Foundation ‘Better housing is crucial for our health and the Covid-19 recovery’ – December 2020

[24] https://www.bregroup.com/services/testing/indoor-environment-testing/natural-light/

[25] Blackpool Council Housing Strategy 2018-2023

[26] WHAT COMMITTEE DID THIS GO TO

[27] WHAT CTTEE DID THIS GO TO?

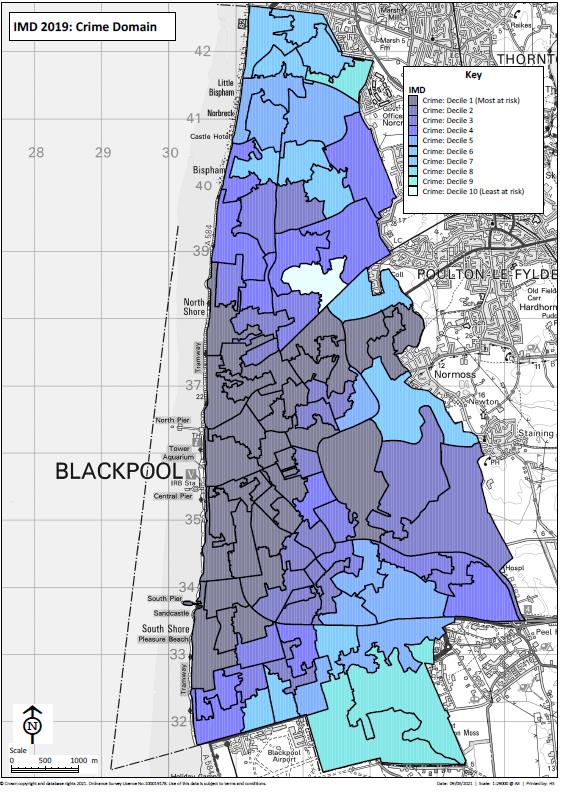

The map below figure 6 shows crime deprivation levels across the Blackpool area. If this is compared to the map at figure 2 it is evident that the areas dominated by small units of accommodation are also the areas that suffer from the highest crime rates.

Figure 6: Spatial distribution of crime deprivation across Blackpool

The relationship between ASB and Selective Licencing schemes is somewhat complex. The review of the South Beach scheme noted that, aside from temporal fluctuations, ASB levels were relatively static over the 5 year period. However, this was considered to reflect the presence of a dedicated ASB Officer and greater engagement between Council and Police staff and the community leading to increased reporting.

Notwithstanding these statistics, operational officers considered the Selective Licencing programme to be so successful that a second Selective Licencing Area was in established in Claremont in 2014. This ended in April 2019 and a review is yet to be published. The latest Selective Licencing scheme was approved in Central area by the Secretary of State in 2018 and came into force in 2019.

The continuing use of this legislative tool demonstrates the ongoing issues in Blackpool and the established links between HMO accommodation and ASB. This recognised connection is one of the driving forces behind the introduction of this Article 4 direction.

Summary

The Council Plan sets out two priorities:

- The economy: maximising growth and opportunity

- Communities: creating stronger communities and increasing resilience

The introduction of an Article 4 direction is considered important to support the Council’s pursuit of its second priority.

This document has set out the extremely high levels of deprivation in Blackpool and the extent to which the most deprived areas of the town are characterised by small units of accommodation that are predominantly privately rented and of relatively poor quality. The abundance of small flats and HMOs reflects Blackpool’s changing fortunes as a holiday resort and presents significant challenges. The easy availability of small and relatively cheap accommodation attracts vulnerable individuals and those dependent upon support from outside the borough, and this demand encourages further provision perpetuating a vicious cycle. The fact that 86% of new benefit claimants originate outside of Blackpool emphasises the fact that the small flat and HMO creation is not driven by locally generated need. In the future, whilst inward migration is expected to fall away, an increase in single person households is expected. However, the increase will be greatest amongst the older age groups for whom C4 HMO accommodation would not be suitable.

The links between poor quality housing, poor health and high levels of anti-social behaviour are well established. Blackpool suffers from relatively high levels of ‘worklessness’, low wages and high benefit dependency. Through its ambitious regeneration strategy, the Council aims to bolster the tourism industry but also diversify the local economy to create new, more stable and more attractive employment opportunities. Parallel to this is the Council’s ongoing work to reduce the supply of poor quality housing and support more balanced and healthy local communities. The creation of sustainable neighbourhoods where people in a position of choice choose to live would reverse the vicious cycles that have characterised Blackpool’s housing market to date.

Given the relatively low house prices in Blackpool, rooms in shared houses are typically sought out by those who cannot afford better. As set out above and evidenced by the benefit claimant data, many of these people are from outside of the Blackpool area. Continued, unregulated provision of HMO accommodation will continue the unsustainable housing cycles described above and undermine the Council’s wider strategies to combat deprivation and establish Blackpool as a desirable place to live and work.

It is acknowledged that a small number of professionals may require short-term affordable housing, such as staff on placement at Blackpool Victoria Hospital. However, this demand is considered to be extremely limited. The harm of requiring proposals for such accommodation to be subject to planning permission is considered to be heavily out-weighed by the benefits of preventing further general HMO provision. It must be remembered that a property occupied by 3 to 6 unrelated individuals choosing to live together as a single household would fall within Class C3(c) and not Class C4.

Geographic extent of the direction

Careful consideration has been given to the geographic extent of this Article 4 direction.

It is accepted that Blackpool’s deprivation is focused on the defined Inner Area of the borough. This could be a logical boundary for an Article 4 direction preventing change of use from C3 dwellings to C4 HMOs. However, as can be seen from figure 2, there are areas of deprivation and concentrations of small housing units across the borough.

If an Article 4 direction were limited to the defined Inner Area, this would likely push the demand for HMO accommodation into peripheral zones that are currently characterised by family housing, and the areas across the borough where small flats and HMOs are prevalent. As there is no need for further C4 HMO accommodation to meet Blackpool’s future housing needs, the additional restriction that would result from extending the direction borough wide is considered to be justified by the increased protection it would offer to the Council’s overall strategy.

Conclusion

There is no need for further HMO accommodation in Blackpool to meet the towns housing needs.

The permitted development allowance for change of use from a family home (use class C3) to a small HMO (use class C4) has the potential to further unbalance Blackpool’s housing market and undermine efforts to establish more balanced and healthy local communities and regenerate the resort.

The direction should apply borough-wide to prevent creep of HMO accommodation and the issues associated with it into existing stable and sustainable neighbourhoods.